Crowdstrike debacle: How do we protect ourselves?

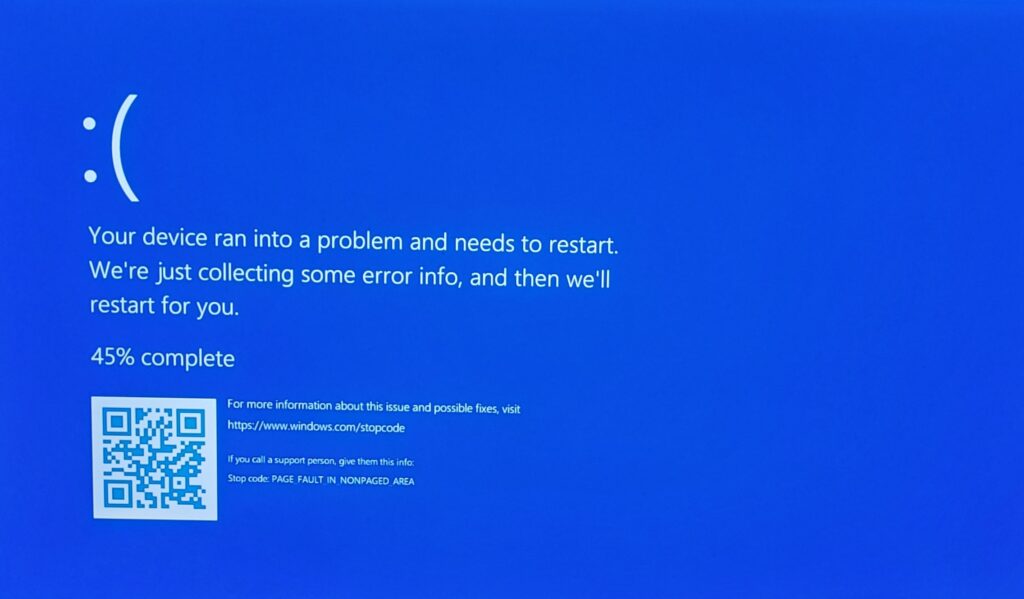

Last Friday, a faulty software update to the anti-malware software Falcon from software manufacturer Crowdstrike caused one of the most serious IT outages in history. In numerous hospitals, banks, TV stations and airports, the screens suddenly went blue. A so-called “Blue Screen of Death” was the only thing that could be seen on the monitors of around 8.5 million affected Windows devices. Since Crowdstrike supplies its software to companies with high security requirements, the critical infrastructure was particularly badly affected. The consequences were devastating: hospitals had to postpone operations, more than 5,000 flights had to be cancelled. While many passengers are still stranded at airports around the world and the technical investigation into the causes has not yet been completed, those responsible in companies, authorities and other institutions are asking themselves how we can reduce our vulnerability to such incidents in the future.

A failure can never be ruled out

In general, risks can be reduced in two different ways: Firstly, the probability of a negative event occurring can be reduced. In this specific case, this includes better quality assurance by software manufacturers and better qualification of products in the supply chain by the companies using them. Since the probability of such an incident can never be reduced to 0%, the negative effects of an event on the organization’s operations must also be mitigated. This includes business continuity management and disaster recovery, also known as BCM/DR. This involves, for example, setting up redundancies so that alternative systems are available in the event of failures.

In recent months, the European Union has launched two legislative initiatives that address these two aspects of risk reduction and impose obligations on both software manufacturers and users.

NIS2 Directive

The NIS2 Directive, which must be implemented into national law in the EU member states by October 17, 2024 (an agreement between the governing parties is still pending in Austria), requires companies in particularly sensitive sectors to implement risk management measures with regard to supply chain security and to define measures to maintain operations and recover after an emergency. As can be seen from the current Crowdstrike incident, it is not just about your own company, but also about the impact on other companies in the critical infrastructure. Since critical sectors are broadly defined and directly affected companies must also hold their suppliers accountable, the NIS2 Directive affects a very large part of the European economy. Although the national law is still a draft, companies have invested heavily in cyber security in 2024 to comply with the directive.

Cyber Resilience Act

The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), which will be passed in the coming weeks and will come into full force in about three years, will require manufacturers of software and hardware products to not only fix and report vulnerabilities and provide updates over a period of five years, but also to establish a quality assurance system for the design, development and testing of digital products. Since importers and dealers are also required to comply, products from US manufacturers such as Crowdstrike that are placed on the European market are also affected by the EU regulation. Software for “searching for, removing and quarantining malware” is an important Class I product and “attack detection and/or prevention systems” is an important Class II product and is even explicitly subject to a stricter conformity assessment than lower-risk software. Violations can result in fines of up to 15 million euros or 2.5% of global sales.

Microsoft will also have to think about a more resilient architecture for its operating system. The Cyber Resilience Act also classifies operating systems as important Class I products. In order to increase the resilience of Windows in the event of a malicious update from a third-party provider and to ensure the availability of Windows devices even after such an incident, Microsoft could, for example, ensure that faulty kernel drivers are no longer loaded after a restart, although it should be noted that this cannot be abused by attackers to deactivate the security product.

Competition Law

If you look at the vulnerability of society as a whole rather than at individual companies, competition law can also help reduce risks. A high level of market concentration means that many companies are affected by such incidents at the same time. Since the Great Famine in Ireland between 1845 and 1849, people have known that monocultures pose great risks. Since Ireland only grew two types of potatoes, crop failures led to major famines. By growing different varieties, the effects of the spread of fungi could have been significantly reduced. As the market leader, Microsoft naturally sees things differently and holds the European Union’s competition law partly responsible for the current incident [1]. In 2009, after a competition procedure with the European Commission, Microsoft had to agree to grant security software manufacturers the same access to the operating system as Microsoft Defender, the malware detection software offered by Microsoft itself. This is an advantage because a bug in the security software could cause all systems to fail in a monopoly situation.

Conclusion

Finally, this incident teaches us to take “zero trust” seriously as a security philosophy. Paradoxically, Crowdstrike promotes its own products as zero trust solutions, but requires its customers to trust its software with highly privileged access to their systems. Anyone who wants to seriously implement the zero trust principle must understand it as a comprehensive strategy for minimizing risk that also takes into account dependencies on manufacturers of “zero trust solutions”.

Reducing the risk of system failures like this is the clear goal of the latest EU initiatives with NIS2 and CRA. But it’s not enough to put IT security on paper in form of a legislation, but IT security must be integrated into the organizations processes and cultures.