Analysis of Crypto used by AppVeyor Secure Variables

We recently investigated AppVeyor’s “secure variables” (aka “Encrypt YAML”) feature. We wanted to understand the crypto and algorithms it uses (which is not documented at the time of this writing) and discovered a few interesting things, which we describe in this blog post.

AppVeyor Secure Variables

AppVeyor is a build software that is available on-premise or in the cloud. AppVeyor can be connected to a (public) source code repository, such as your GitHub repository, and be configured to automatically build a new version of the software whenever code in the repository is changed. The AppVeyor build configuration file (appveyor.yml) can also be checked in to a source code repository to make use of its collaboration and versioning features.

However, certain information in this appveyor.yml file might be sensitive (e.g. access credentials to other systems or services required during the build) and should not be visible to all developers (or to everyone in case of open source projects). The AppVeyor secure variables feature allows you to encrypt sensitive data before putting it into the appveyor.yml file. So only AppVeyor can decrypt this data to obtain the original value and use it during the build process. These encrypted values can e.g. be used in the appveyor.yml in configurations for environment variables or within webhooks.

The first thing to be aware of is that secure variables are only protected from users without write access to the appveyor.yml. Users with write access to this file can obtain the decrypted value. This can be done by e.g. just printing the secure variable to the build log (the secure variable is automatically decrypted by AppVeyor).

Secure Variable Encryption

We analyzed properties of the encryption of secure variables.

We found out that the used cipher is a block cipher and has 128 bit (16 bytes) block size. This can be discovered by increasing the length of the plaintext. If the ciphertext length increases equally to the plaintext length, the used cipher is a stream cipher. If the ciphertext length increases in blocks, then it is a block cipher. In the case of a block cipher, one can easily find out the block length by observing the increase in length of the ciphertext.

We did some further tests to find out more.

Our test used the following secure variable (unencrypted):

Bearer SecretToken123456789012345678901234567890The hexadecimal representation of this string is:

42 65 61 72 65 72 20 53 65 63 72 65 74 54 6F 6B

65 6E 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30 31 32 33 34

35 36 37 38 39 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30When using the Encrypt YAML feature for this variable, AppVeyor returns the following Base64-encoded encrypted string:

FVwaQuowgIbDmPo987vdYrmGEHeelN7l6ni8MTzouU3jtrE8/9w6tYSuq84DHJbXhMQKpxqfZOTRIH0g/flKjg==After Base64 decoding, the hex representation is:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 10 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 D7

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8EHere we can already see that our encrypted ciphertext has 16 bytes more than the plaintext. This is probably due to padding and allows us to infer that the block size of the ciphertext is 16 bytes.

To find out more about block size and the mode of operation, we modified the following bytes of the ciphertext:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 11 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 D7

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8EThis ciphertext decrypted to the following value:

Bearer SecretTokL Q4▒u5i?y▒▒'15668901234567890The hexadecimal representation of this string is:

42 65 61 72 65 72 20 53 65 63 72 65 74 54 6F 6B

4C 09 51 34 FD 75 35 16 69 3F 79 FD FD 27 31 1C

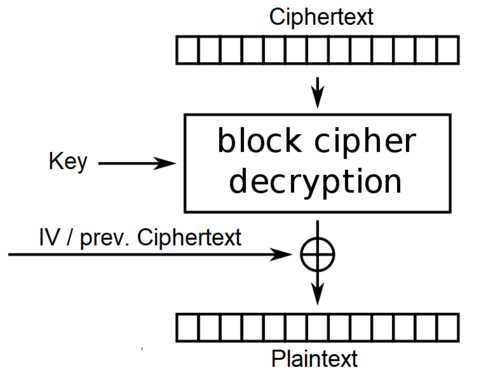

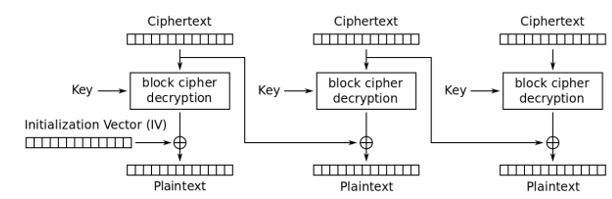

35 36 36 38 39 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30We can see that a change of the third byte in the second ciphertext block changed the whole second plaintext block and the third byte of the next plaintext block. This perfectly matches the behavior of the cipher mode CBC as displayed in the following figure:

Generally, in CBC a change in a byte of a ciphertext block at index X directly affects all bytes of the same ciphertext block and the byte at index X of the next ciphertext block. The observed behavior further confirms that the encryption algorithm is a block cipher with 16 bytes length.

Our test didn’t lead to an error but decrypted normally. From that we can infer that the ciphertext is not integrity protected.

In many cases missing integrity protection has security implications. In combination with the CBC cipher mode, this can result in so called “Padding Oracle” attacks. These attacks exploit the lack of integrity protection and some properties of CBC mode and PKCS#7 padding and allow attackers to fully or partially decrypt ciphertext!

This means, AppVeyor might be vulnerable to Padding Oracle attacks. Notably, as laid out at the beginning of the post, anyone with write access to the appveyor.yml can decrypt values by design. Thus, a Padding Oracle would have no security implications in AppVeyor. Nevertheless, for more curious readers, we briefly describe our analysis of a potential Padding Oracle in AppVeyor.

Padding Oracle in AppVeyor

To be able to exploit a Padding Oracle, one must obtain a valid ciphertext and be able to provide arbitrary ciphertext to the decryption system. Furthermore, it must be possible to distinguish the following cases (e.g. by different error message, by timing, or other means) when decrypting ciphertext:

- A given ciphertext decrypts to a valid plaintext

- A given ciphertext decrypts to a malformed plaintext (e.g. with non-ASCII characters) and has valid padding

- A given ciphertext has invalid padding

This information, combined with the knowledge of how CBC and PKCS#7 work and some basic logic, is enough for an attacker to decrypt most of a given ciphertext. To confirm the existence or non-existence of a potential Padding Oracle in AppVeyor, we performed the following tests.

We used a secure variable (the Bearer-token from above) to let AppVeyor authenticate against our web server. On the web server we received:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Authorization: Bearer SecretToken123456789012345678901234567890

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8858

Connection: Keep-AliveThis matches the behavior of case 1.

We then modified the third byte of the second block and again let AppVeyor authenticate against our web server. This time we received:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Authorization: Bearer SecretTokL Q4▒u5i?y▒▒'15668901234567890

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8860

Connection: Keep-AliveThis matches the behavior of case 2.

Lastly, we crafted a ciphertext that causes bad padding. For that we changed the last byte of the third block. Due to CBC mode, this change should not only scramble the third block, but also change the last byte of the fourth block, which is our padding. Since padding needs to have a specific structure in PKCS#7, this change should cause incorrect padding. We used the following ciphertext:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 10 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 00

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8EWith this ciphertext we let AppVeyor authenticate against our web server one last time. The result was:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8840

Connection: Keep-AliveThis matches the behavior of case 3.

Is this a problem? Yes, it is! Because this behavior exactly matches the definition of a Padding Oracle. An attacker could now continue this attack as described in this blog post and could obtain most or all of the plaintext from the ciphertext. Particularly, if an attacker knows the initialization vector, he/she can obtain all of the plaintext. If an attacker doesn’t know the initialization vector, he/she could obtain the plaintext for the whole ciphertext except the first ciphertext block. However, in many cases the first ciphertext block can be guessed or obtained from the system.

As mentioned before, due to the design of the secure variables feature altogether, there seem to be no security implications of this issue in AppVeyor.

Conclusively, in this article we showed:

- How AppVeyor’s secure variables work.

- The encryption used for secure variables.

- How this encryption mode and lack of integrity protection can, in principle, lead to Padding Oracle attacks that allow the decryption of most or all of the ciphertext.

This analysis was performed in cooperation with Daniel Ostovary from SignPath.